The other day, a friend asked me about the work I do, and why working with First Nations communities and cartography was so important to me. I was struck with one question in particular: “Why do you need to make maps? Aren’t there already a lot of maps already out there?” The short answer is simple – “Yes AND No”. The history of cartography as it pertains to Indigenous communities is far more complex and difficult to explain in one short answer, however.

In North America (as in many other countries), maps have been used by European settlers to relegate Indigenous communities to the small parcels of land we now call Reserves (in Canada), and Reservations (in the United States). Jordan Engel, the founder of a project called the “Decolonial Atlas”, states that, for many First Nations, “there is no truth in cartography”. Engel explains his viewpoint further:

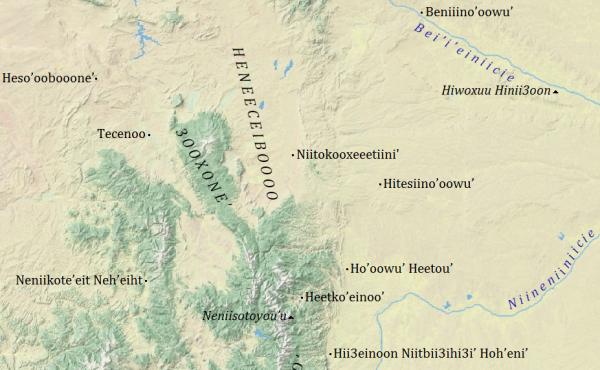

“Colonial powers, without the consent of Indigenous people, drew up imaginary political borders, which, more often than not, don’t reflect any real natural or cultural boundaries”.

For anyone interested, Engel’s project can be viewed in more detail at www.decolonialatlas.wordpress.com. It is important to interject here that the statement “there is no truth in cartography” is not completely accurate.

I believe that there is always an inherent truth to be found in maps and cartographical charts. Maps provide us with a picture of how we understand the world around us, and what the places we chose to display mean to us and for us. Perhaps more accurately, the maps that many of us use and understand today hold little truth for First Nations groups. This is because of the way that Native place and space was changed by European settlers and redrawn to exclude Indigenous peoples from the land and resources they had long-standing sovereign rights to. What became ‘truth’ for the settler was little more than a paper-thin ‘lie’ for First Nations communities who could no longer access important resources and sacred cultural sites. One of the simplest ways to rewrite history using cartography is through changing the names of the places listed on the map.

Some of you might remember last August 2015, when Barack Obama visited Denali National Park in Alaska. The tallest mountain in North America, standing 6,190 metres above sea level, can be found in Denali National Park. This mountain was named Mount McKinley by a gold prospector in 1896, in honour of then President William McKinley. The Koyukon Athabascan people who called the area home knew this mountain as Denali, or “The Great One”, however. From 1913 to Obama’s visit in 2015, the naming of Mount McKinley produced much conflict over the proper placename. Last August, Obama official changed the name of the mountain back to Denali – and with this name change came a different understanding of the region’s and the people’s history.

Maps lay out specific understandings of place and space. Place names hold specific history, use, ownership, and sovereignty over the places drawn on the map. What is important about maps is that they allow others to control spaces, people, and resources. Even more importantly is that these same maps can be redrawn and created to include cultures and people which were originally drawn out of the map. Most importantly, in the words of cartographer Doug Aberley, “Maps can show a vision for the future more clearly than thousands of words”.[1]

This is why working with cartography and First Nations communities is important to me. We can use the same tool (the map) which marginalized these communities in the first place to restore social justice rights, improve food security and resource capacity, create better cultural understandings, and establish new awareness for the histories of the places we live in. By engaging marginalized communities in collaborative research and community mapping, we may ultimately create a better and more sustainable future for us all.

[1] Aberley, D. 1993. Boundaries of Home: Mapping for Local Empowerment. New Society Publishers. Gabriola Island, BC.